Well – I’m home! I’m in California, at least

semi-permanently. Alhamdoulilah. I actually arrived back on US soil almost

three weeks ago now, but I’ve been putting this off. “This” being “the last

Peace Corps blog post EVER.” Until, of course, I retire and serve as a PCV in

Fiji. But until then, there’s only this. It kind of feels like a lot of

pressure. It’s been two years! That’s a long ass time! Peace Corps, geez. I did

it. Anne met Africa. Good lord.

…Anyway. I should start off by saying that my last couple weeks

in village and in Tamba were really good for the most part. The building

project kept me occupied until the very end, which was good for my mental

state. Saying goodbye was really hard, though. My first plan was to host a big

feast for my family and friends the day before I left, get through the teary

goodbyes that night with as little embarrassment as possible, then bike out of

village the next morning as the cocks crowed (or a little later, as they start

crowing at 3:50 a.m. – dumb birds) but before everyone else was awake. Well, we did have an amazing going-away

feast, complete with goat and vermicelli and potatoes. Delicious. Souleymane kept

telling me “We don’t even eat this well on Tabaski!” There was so much food, it

took my host parents about 30 minutes to allocate different amounts to

different bowls, with much arguing: “Ok, this bowl is for the masons, this one

is for the teachers – put some more meat in that! – this one is for your

brother, this one is – hey! There’s not enough sauce in there! – for the

village chief, this can be for your sister, she’ll be mad otherwise…” And so

on. Basically, it was a hit. We all lounged around in a food coma for the rest

of the afternoon.

|

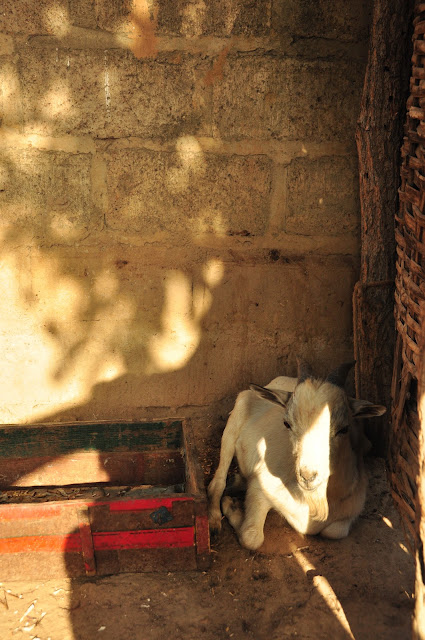

| I named him "Lunch" |

When night came, and I tried to say goodbye, they wouldn’t

let me. They would only say “Fo saxooma!” (‘Til the morning!) which thwarted my

as-little-crying-and-drama-as-possible exit plan. It was fine though, and

probably better that way. I still left in the morning, but limited my good-byes

to my compound. They were tearful but quick, and I got on my bike and biked out

of village, trying not to cry too hard on the way out (the path is hard to

navigate in the best of circumstances). I’m not trying to invoke sympathy, I’m

just telling it like it was. I miss my family. I miss the kids. It was really,

really hard to leave Bira.

|

| Ami and Aileen examining my newly henna-ed feet |

| The fam. This photo is still missing about 5 kids |

After I was moved out of village, however, things were much

easier. Sure, saying goodbye to my PCV friends sucked also, but I know that if

I want to see them (and I do), I will. We have facebook and phones and

airplanes and trains and a fairly reliable network of highways. Life here is

easy.

That brings me to my next thought. I’ve been really happy

since being home. This is a type of happiness I don’t think I’ve ever really

experienced. I was trying to pinpoint what exactly was going on and I’ve come

to the conclusion that the culprit is plain ease of living. Yes, sure, I lived

here for 23 years before going to Senegal, and my life was easy. But I didn’t

know any different. I took it for granted. In Senegal, although I certainly

felt happy most of the time, it was just harder to do things. Even simple tasks

like going to the store involved bikes or cabs, ridiculous heat, sweat,

multiple languages, and frequently verbal harassment. Any longer sort of journey

was an ordeal at best. Crowded cars and buses, heat (again), breakdowns,

arguments, bargaining, reckless drivers and long waits made many trips a

nightmare. I expected this, and it was never surprising, but it didn’t help

much. Once I stayed in Tamba for a full 4 extra days just because I couldn’t

face the journey back to village – and I was only 55km away. In Senegal, I was

always subconsciously on the defensive. Before going anywhere or doing

anything, you had to “gird your loins,” as I believe the saying goes. But not

here. My subconscious’ defensive attitude is gone.

So, that is the root of my newfound, carefree happiness. I

can go where I want to when I want to. The weather is perfect. Food is healthy

and easy to come by. My showers are hot and I can wear real clothes without

sweating through them in ten minutes. I’m not the most interesting thing

walking down the street, and strangers don’t yell at me as a matter of course. My

bed is comfortable and I don’t have to worry about if my mosquito net has

holes. There are no rats having parties in my bedroom every night. Basically

all the things that I took for granted before Peace Corps. I know this is

unlikely to last, but I’m hoping it’ll hang on for as long as possible. It’s a

background kind of happiness, but it’s great.

Add that to my more specific joys of seeing family and

friends and good beer and you can imagine how I’m feeling right now. I guess

this has a flipside too, though. I’m expecting America to be great in all ways

(the “honeymoon phase”), so when something small and unimportant and unpleasant

happens – the homeless guy cursing out fellow passengers on BART, for example –

it’s kind of a rude wake-up call.

“Whaaaaat? I left Senegal for THIS?” Or, if I see a mosquito – “What is

this s**t?!”

I guess no place is perfect. But I am going to enjoy my life

here fully. I’m going to take showers that are just a bit too long, I’m going

to sing along to the radio in the car, I’m going to drive to the grocery store

and marvel at the simplicity of it all. I’m going to work in a nice office and

wear close-toed shoes and go to school and forego using shampoo as an

all-purpose product and look like a real 25 year-old American woman. I’m also

going to call my host family every month. Baby Aileen is walking now,

apparently, and they say they miss me.

I miss them too. I’ll always be Fanta Savane in their minds, and in

mine.

A lot of people have asked me what the greatest thing I took away from this experience is. I would say: people. People are people, no matter where they live or in what state. Whether American or Senegalese or Amazonian tribesman (just guessing on that one), we all love our families and have wonderful friends. We have communities that support one another. We are joyful, sad, angry, amused, and frustrated by turn. It doesn't matter whether your roof is made of straw or, or...carbon fiber (I tried to think of something high-tech). We are the same in all the things that matter. Realizing this, for me, makes the whole world seem a little less foreign than it did before.

So, Peace Corps: the hardest thing I've ever done, but incredibly worthwhile. As a fellow RPCV (who got back from Ukraine 10 years ago and is now a lawyer) told me: "Whenever I face a problem here, I think, is this as hard as my first six months in (insert country here)? Nothing has been." I think my experience will continue to serve me well in that regard. I'm more fearless and confident that I ever was pre-Senegal. I've done things that most people only dream of (some of them in their nightmares). It's not bragging; it's the truth. I feel good.

A lot of people have asked me what the greatest thing I took away from this experience is. I would say: people. People are people, no matter where they live or in what state. Whether American or Senegalese or Amazonian tribesman (just guessing on that one), we all love our families and have wonderful friends. We have communities that support one another. We are joyful, sad, angry, amused, and frustrated by turn. It doesn't matter whether your roof is made of straw or, or...carbon fiber (I tried to think of something high-tech). We are the same in all the things that matter. Realizing this, for me, makes the whole world seem a little less foreign than it did before.

So, Peace Corps: the hardest thing I've ever done, but incredibly worthwhile. As a fellow RPCV (who got back from Ukraine 10 years ago and is now a lawyer) told me: "Whenever I face a problem here, I think, is this as hard as my first six months in (insert country here)? Nothing has been." I think my experience will continue to serve me well in that regard. I'm more fearless and confident that I ever was pre-Senegal. I've done things that most people only dream of (some of them in their nightmares). It's not bragging; it's the truth. I feel good.

So the classroom was almost completed as I left Bira. By

now, it should be open for business! I will call my counterpart to get

confirmation. I wasn't able to raise enough for two whole classrooms, but you guys donated enough for one classroom plus a bunch of other things that the school needed. My school director and I sat down and worked out a way to pay for A)

an office and office furniture (right now the teachers use their own huts for

work and supply storage… and they burned down a couple weeks ago), B) Solar

power for all the classrooms, so that students can study at night, and C) a gift of school supplies to every

student in Bira at the beginning of next year. I would say MISSION COMPLETED –

and another huge THANK YOU! to all the donors. Thank you thank you thank you! Here’s the price breakdown,

if you’re interested (this is in CFA):

TOTAL AMOUNT: 2, 955.000

400.000 to mason

90.000 – bricks

497.000 – roofing materials

820.000 – cement

100.000 – transport

10.000 – personal transport

40.000 – pulling water

17.000 – unloading fees

30.000 – scrap metal, soldering/painting

216.000 – more roofing

65.000 – door and windows

670.000 – solar power, bureau, school supplies

Til next time -

Anne/Fanta

| The classroom, almost complete, from outside |

| ...and from the inside |

|

| The mason and his assistants goofing off |